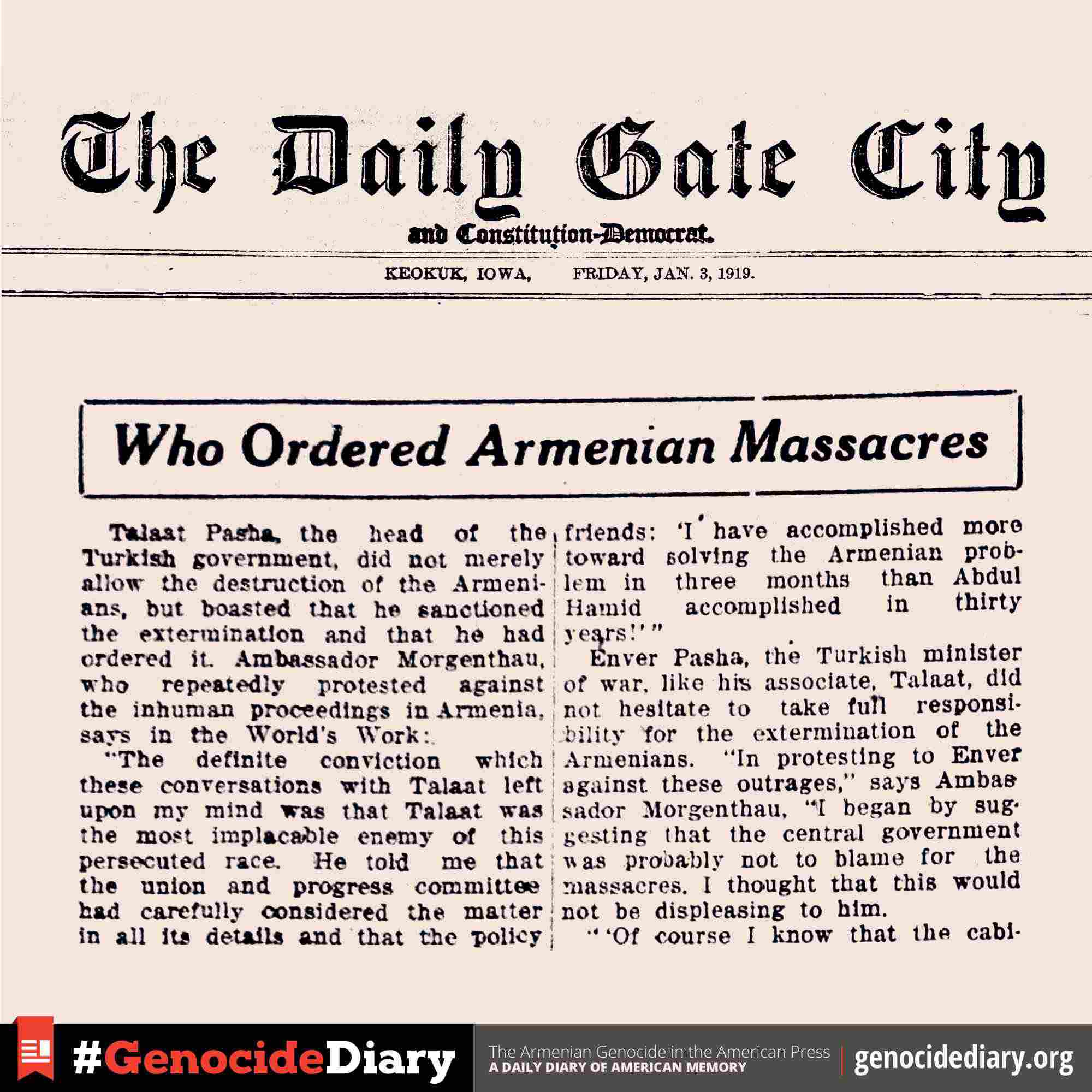

Who Ordered Armenian Massacres

- DATE 3 Jan , 1919

- POSTED IN Iowa, United States

Talaat Pasha, the head of the Turkish government, did not merely allow the destruction of the Armenians, but boasted that he sanctioned the extermination and that he had ordered it. Ambassador Morgenthau, who repeatedly protested against the inhuman proceedings in Armenia, says in the World’s Work:

“The definite conviction which these conversations with Talaat left upon my mind was that Talaat was the most implacable enemy of this persecuted race. He told me that the union and progress committee had carefully considered the matter in all its details and that the policy which was being pursued was that which they had officially adopted. He said that I must not get the idea that the deportations had been decided upon hastily; in reality they were the result of prolonged and careful deliberation. To my repeated appeals that he should show mercy to these people, he sometimes responded seriously, sometimes angrily, and sometimes flippantly:

“’We have been reproached,’ he said, according to this interviewer, ‘for making no distinction between the innocent Armenians and the guilty; but that was utterly impossible, in view of the fact that those who were innocent today might be guilty tomorrow!’

“’It is no use for you to argue,’ Talaat answered, ‘we have already disposed of three-quarters of the Armenians; there are none at all left in Bitlis, Van, and Erzerum. The hatred between the Turks and the Armenians is now so intense that we have got to finish with them. If we don’t, they will plan their revenge.

“’We base our objections to the Armenians on three distinct grounds. In the first place, they have enriched themselves at the expense of the Turks. In the second place, they are determined to domineer over us and to establish a separate state. In the third place, they have openly encouraged our enemies. They have assisted the Russians in the Caucasus and our failure there is largely explained by their actions. We have, therefore, come to the irrevocable decision that we shall make them powerless before this war is ended.’

“One day Talaat made what was perhaps the most astonishing request I had ever heard. The New York Life Insurance company and the Equitable Life of New York had for years done considerable business among the Armenians. The extent to which they insured their lives was merely another indication of their thrifty habits.

“’I wish,’ Talaat now said, ‘that you would get the American life insurance companies to send us a complete list of their Armenian policy holders. They are practically all dead now and have left no heirs to collect the money. It, of course, all escheats to the state. The government is the beneficiary now. Will you do so?’

“’You will get no such lists from me,’ I said, and got up and left him.

“Talaat’s attitude toward the Armenians was summed up in the proud boast which he made to his friends: ‘I have accomplished more toward solving the Armenian problem in three months than Abdul Hamid accomplished in thirty years!’”

Enver Pasha, the Turkish minister of war, like his associate, Talaat, did not hesitate to take full responsibility for the extermination of the Armenians. “In protesting to Enver against these outrages,” says Ambassador Morgenthau, “I began by suggesting that the central government was probably not to blame for the massacres. I thought that this would be displeasing to him.

“’Of course I know that the cabinet would never order such terrible things as have taken place,’ I said. ‘You and Talaat and the rest of the committee can hardly be held responsible. Undoubtedly your subordinates have gone further than you have intended. I realize that it is not always easy to control your underlings.’

“Enver straightened up at once. I saw that my remarks, far from smoothing the way to a quiet and friendly discussion, had greatly offended him. I had intimated that things could happen in Turkey for which he and his associates were not responsible.

“’You are greatly mistaken,’ he said. ‘We have this country absolutely under our control. I have no desire to shift the blame on our underlings, and I am entirely willing to accept the responsibility myself for everything that has taken place. The cabinet itself has ordered the deportations. I am convinced that we are completely justified in doing this owing to the hostile attitude of the Armenians toward the Ottoman government, but we are the real rulers of Turkey, and no underling would dare proceed in a matter of this kind without our order.’

“Enver tried to mitigate the barbarity of his general attitude by showing mercy in particular instances. I made no progress in my efforts to stop the program of wholesale massacre, but I did save a few Armenians from death. One day I received word from the American consul at Smyrna that seven Armenians had been sentenced to be hanged. These men had been accused of committing some rather vague political offense in 1909; yet neither Rahml Bey, the governor general of Smyrna, nor the military commander believed that they were guilty. When the order for execution had reached Smyrna these authorities wired Constantinople that under Ottoman law the accused had the right to appeal for clemency to the sultan. The answer which was returned to this communication well illustrated the extent to which the rights of the Armenians were regarded at that time:

“’Technically, you are right; hang them first, and send the petition for pardon afterward.’

“In all my talks on the Armenians the minister of war treated the whole matter more or less casually; he could discuss the fate of a race in a parenthesis, and refer to the massacre of children as nonchalantly as we would speak of the weather.”